Journalists have become figures of hate in many quarters where they previously enjoyed something approaching respect. Derided for poking their noses into other people’s affairs, irrespective of what dens of iniquity they may unmask, and seen as pariahs at disaster scenes and parasites at public events, the plight of the hack continues to nosedive. With the internet oozing disinformation, uploaded by mischief makers and naïve DIY news-gathers, journalists are also seen as being sloppy and sensational online, not helped by the pressure for huge eyeball rates to drive up revenues and replace dwindling hard copy sales.

But journalists are not just operating to line their own and their bosses’ pockets, or are they? There may be some conflict here, but the pure concept of journalism as a bridge between what’s happening in the world – embracing both the foul and the fabulous – and the public could not be more fraught. Putting aside the many theories on objectivity, there appears to be an increasing lack of tolerance when views are expressed that don’t chime with the reader, and journalists are regularly in the firing line.

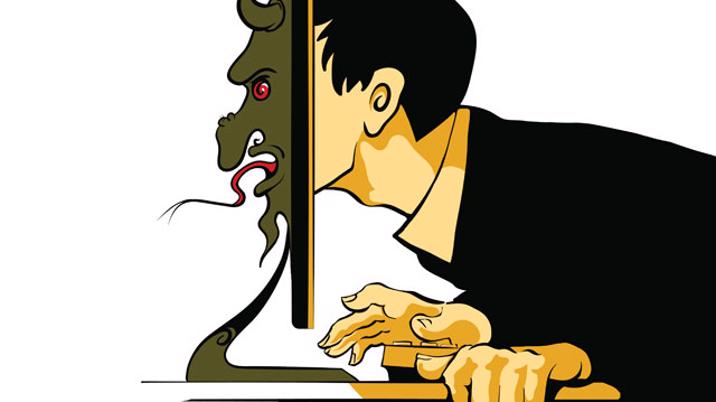

Journalism in democratic societies involves the discussion of concepts, decision-making and all the factors which help people to understand world dynamics and to play a part in the progress of civilisation. Journalists have a duty to challenge and question those in power, a role anchored in concepts of the media as the fourth estate and should cover a wide range of political opinions and positions. But for some individuals, this ever widening panorama, made possible through the internet and other technological advances, has had the opposite effect. They are looking through the wrong end of the telescope and completely missing the big picture. This has manifested itself with a growing army of internet trolls.

The trolling psyche

There are plenty of ‘troll’ definitions. Hiding behind fake profiles gives them the courage to be more vindictive over sensitive topics. Some infiltrate groups posing as like-minded members and then strike from within causing mayhem, embarrassing and insulting people for their own amusement. What they come out with isn’t necessarily their honestly-held belief either. They generate false or incorrect utterances to encourage negative or aggressive responses. They are attention-seeking and like to smash people’s confidence. Perhaps one of the worst things for journalists is that an encounter will take time to sort out. As Ward Cunningham once said: “A troll is a time thief… That is what makes trolling heinous.”

Media owners generate controversy

To a large extent, media owners have orchestrated a high level of engagement with their audiences. With falling hard-copy revenues, they turned to the internet with varying success to lure advertisers onto their webpages. The use of search engine optimisation to draw in readers was quickly harnessed by some outlets, for instance MailOnline. Employing controversial columnists, like Katie Hopkins, helped to develop the audience, although she was let go after tweeting of the need for a “final solution” after the 2017 Manchester arena bombing. She likewise overstepped the mark at The Sun and the LBC radio network. Sanna Trygg noted in 2012: “Trolling and other negative behaviour on magazine websites is widespread, ranging from subtly provocative behaviour to outright abuse. Publishers have sought to develop lively online communities, with high levels of user-generated content. Methods of building sites have developed quickly, but methods of managing them have lagged behind.”

Media outlets seeking to boost audiences through titillation and controversy have effectively built troll-baiting and troll-feeding into their business models. With the thought of any kind of censorship making journalists’ skin crawl, there was reluctance to police the area too heavily, but gradually, and largely for legal reasons, moderation became a staple. The costs grew along with the flood of comments as more people engaged online. But then came a key moment. Respected online journal PopularScience.com switched off the comments section in 2013. Online Content Director Suzanne LaBarre posted: “Comments can be bad for science. That’s why, here at PopularScience.com, we’re shutting them off.” They were as committed to fostering lively, intellectual debate as they were to spreading the word of science far and wide, but: “The problem is when trolls and spambots overwhelm the former, they diminish their ability to do the latter… even a fractious minority wields enough power to skew a reader’s perception of a story.”

A steady stream of media organisations then began to close down or restrict the comments section, arguing it was too costly to effectively police. But media owners still wanted online discussion so the responsibility fell more to individual journalists responding via social media. Incidentally, they were also expected to promote stories and upcoming issues of their papers. What training did they have for dealing with trolls? None. What incentives did they have? Well, keeping in with the editor, and for freelancers, further work.

Case studies – toughen up, tone it down or quit

Journalists have been left to fend for themselves. For instance, shortly after troll attacks on BBC Political Editor Laura Kuenssberg, deputy director Fran Unsworth said their female stars needed to learn to “disassociate” themselves from online abuse.

Well-known British journalist Julie Burchill is well documented for her hard-hitting stance following a number of high profile spats. There are some unhappy endings, however. In February 2014, the Australian model turned television presenter Charlotte Dawson committed suicide. She had survived one suicide attempt and waged a public war against trolls, but Twitter comments such as: ‘please hang yourself promptly’ and ‘neck yourself you filthy s***’ intensified.

Attracting less attention was an incident in 2013 when Emma Barnett, Women’s Editor at The Telegraph, Guardian columnist Hadley Freeman and Independent columnist Grace Dent, were sent a bomb threat tweet. Barnett had ignored it and gone to the pub. But police took the issue seriously and the man, who thought he was untraceable, was tracked down and cautioned. Barnett said: “More people don’t want to provoke others, so they start to self-censor what they say if they are trolled. But if you’re a journalist, your job is to provoke.”

Journalist Linda Grant quit the Guardian after being targeted. A Women in Media survey of 1054 Australian journalists found 41 per cent of staff journalists and 18 per cent of freelancers were attacked by trolls. According to a Demos report, around five per cent of the tweets a female journalist receives are derogatory or abusive, compared to under two per cent for male journalists. A survey by the National Union of Journalists and University of Strathclyde showed reporters had received death threats and “feared for their safety” with more than 80 per cent saying cyber-bullying extended beyond working hours. More than 80 per cent had not reported the abuse to police, more than half said it had affected how they worked and more than 40 per cent did not tell their employer.

Journalists’ experiences

My research involves interviews with 20 journalists and 40 journalism undergraduates. Many of the journalists had similar stories and the abuse was not restricted to women. An experienced national journalist, who vowed not to be intimidated, said his Facebook page was destroyed after he infiltrated and exposed a Fascist party. “If we gave in to threats and intimidation from people like that, they would continue to advance their cause unchecked which wouldn’t do at all. We’re asked to make a story as good as we can and as controversial as possible and to drive the agenda for the next day. I’m sure that’s a lot to do with driving traffic to online and social media.”

A seasoned male journalist received abuse and threats over a blog about the political astuteness of Pussy Riot. He said: “There’s so much hypocrisy going on the part of online newspapers. Of course the abuse is part of their business model because it creates clicks, which create advertising revenue… This will only change if the advertising model changes, when advertisers realise having their ad next to a lot of bile doesn't do them any good and they stop measuring attention in terms of mere clicks. But I’m not holding my breath.”

Journalists new to the industry were generally more guarded. One said: “I think it is best to stay away (from heated debates online) and avoid confrontation as everyone is entitled to their opinion and it says more about the commenter than you.” Another said, following online abuse, they now “have to think very carefully about wording”. Three other newcomers said bad experiences affected what they wrote and their ability to freely express themselves. One incident involved a ‘troll-fest’, a coordinated attack from a group troll Facebook account. This involved hundreds and hundreds of instant messages and comments.

Another incident involved a reader being upset about a comment. “The blog editor decided to remove the section that had outraged the reader. Afterwards, I decided to dilute my opinions and observations down so as to avoid such moments in the future.”

The reporters only sought information on how to deal with attacks during and after the event.

A BBC news editor said they had restricted their below the line comments to two or three due to the high cost of moderating sites after stories were being “hijacked” by extremists, including fascists, homophobes and people with sexist views. “When you spend too much of the licence fee money on external moderators weeding out extremist views then the ends don’t justify the means,” he said.

Employers had done nothing, or very little, to prepare staff for the inevitable flak generated via their online profiles. Support was minimal. Journalists and students alike felt more should be done to prepare them. The biggest danger areas, unsurprisingly, were gender (especially feminism and looks for women), politics, race, religion, disability and, in sports, stating a football allegiance.

Implications and solutions

Clearly some journalists were moderating their own comments to avoid a backlash. Women, often faced with rape and death threats, are particularly vulnerable. Some of the best tactics for thwarting trolls were devised by feminist groups. Disturbingly, my research showed some journalism undergraduates were already experiencing some of this vitriol online. Learning to ‘button up’ at such a tender age could have repercussions when embarking on a career in journalism. A subconscious fear of generating abuse could lead to a more sanitised approach to thorny topics. There have been some moves to combat online thugs. Recent high profile cases have prompted action from social media giants and the government to protect the young and outlaw anonymous trolls. This includes setting up a new national police hub to crack down on online hate crime enabling the monitoring of social media posts and unmasking of anonymous users posting hateful material. This has, however, generated concerns from some free speech groups and even the former European Commissioner for Human Rights, Thomas Hammarberg, who said: “People are at a loss to know how to apply rules for the traditional media to the new media.”

In response to demand from my research sample, I devised a survival guide, an evolving process, for our students and for newcomers to the industry. There are perils online and a duty for journalists to safeguard the open channels of communication. Being prepared and knowing who to go to for help is important. You wouldn’t let anyone loose on the road until they’ve passed their driving test, so why allow young journalists to enter the shark-infested water of online journalism without adequate training. It is critical that new generations of journalists maintain the principles of freedom of the press. They should feel confident and safe about expressing themselves online, and be both prepared and equipped to deal with situations if targeted.

This is an abridged version of an article taken from the recently published book Anti-Social Media? The Impact on Journalism and Society, edited by John Mair, Tor Clark, Neil Fowler, Ray Snoddy and Richard Tait.

Published by: Abramis

ISBN: 9781845497293