A question of punctuation

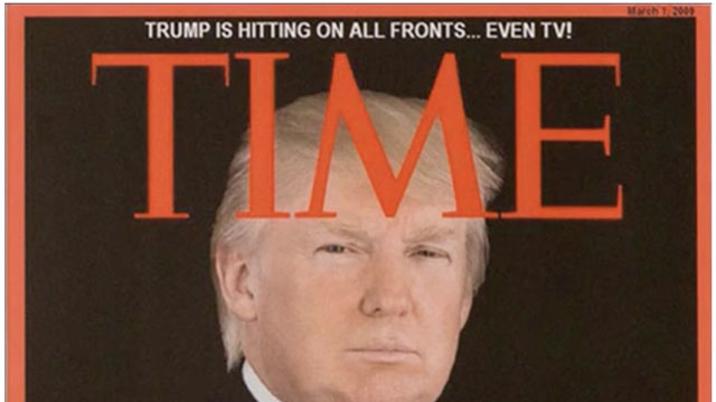

The fake cover of Time magazine that was given pride of place in many of Donald Trump’s golf clubs was rumbled on two counts: one, the red border was the wrong depth and two, there were two exclamation marks in the copy. Time magazine claims that it never uses exclamation marks.

This last fascinated me. Time magazine’s other contributions to style have often been lampooned (“backward ran sentences until reeled the mind” as the New Yorker sniggered in the thirties) but it had never before struck me that the absence of exclamation marks was such a token of earnest. Even Ellen DeGeneres’ coming-out cover from 1997 just had the lines “Yep, I’m gay” without any further emphasis. This implies that they were said in a matter of fact “nothing to see here” fashion. As soon as you put exclamation marks at the end of even the most mundane sentence you are making it into a loud declaration demanding of a round of applause. Many magazines are in the habit of putting screamers at the end of every pull-quote, thus making “I like sausages!” sound like a confession that has been wrung from the interviewee in a moment of weakness rather than a statement which would otherwise have been unworthy of even being transcribed.

Time has an unblemished record as far as this is concerned. The only exception I could find was a cover marking the engagement of Charles and Diana which had an exclamation mark in the line “Three cheers!” There was something in that particular usage that seemed to be gently lampooning what is, after all, an old school, jolly hockeysticks Britishism.

Thinking about Time set me looking at whether other magazines habitually reach for the fifth gear which the exclamation point traditionally provides. GQ don’t appear to use them but Glamour do! Good Housekeeping get by without them. Cosmopolitan clearly couldn’t!

Then there are the magazines which have an exclamation point built into their very names. Kerrang! was not the first here, although they have since been one of the most enthusiastic users of the point. A recent survey turned up a Kerrang! cover with no less than thirteen screamers on it. Shoot! was doing it in 1969. Oh Boy! was doing it not long after. Hello! had to have a screamer because the Spanish original Hola! so clearly did. Therefore OK! had to do the same thing, even though the expression doesn’t demand it. Interestingly, Now doesn’t have one. This may be because the previous user of that title, James Goldsmith’s news magazine Now!, did and whenever Private Eye referred to it as Talbot!, the addition of the exclamation point only seemed to increase its sting.

There was a time when the exclamation mark was largely confined to the people who wrote the speech bubbles in children’s comics. It’s now enjoying a fresh ubiquity thanks to the email. While the emails I send are terse to the point of rudeness, I have come to realise that any emails I get from people under the age of forty will have exclamation marks throughout, even if the message is just “OK”. There is clearly a generation of people who believe that this is the punctuation equivalent of service with a smile. I am further told that this may be just a side effect of the feminisation of discourse. You will not be surprised to hear that somebody has already done a study of Gender and the Use of Exclamation Points in Computer-Mediated Communication. I shall take that and study it on holiday.

Posh & Polished

The first time I was introduced to Nicholas Coleridge, it was in a sandwich bar round the corner from my then office in Carnaby Street. It must have been at some point in the early 80s. It goes without saying that I’ve never seen Nick Coleridge in a sandwich bar since. In posh restaurants, of course; at any place where advertisers gather, certainly; just like Jeeves, Nicholas didn’t enter a room - instead, like Wodehouse’s hero, he shimmered in, materialised or oozed. Nobody does smooth like Nicholas.

I once chaired a panel for the PPA in which former editors talked about what they did in their new managerial capacity. Nick simply rocked up and read his diary, which was just a succession of chats with editors, lunches with big advertisers and head-round-the-door appearances at functions run by smaller advertisers. His retirement from Condé Nast after a long and distinguished career deprives the magazine industry of one of its last remaining characters, one of the select few who could just turn up at any function and be confident of being the physical embodiment of the brand values of an entire publishing house – in his case posh, polished, well-informed and glinting with mischief.

Knowing me, knowing you

The BBC Radio Player wants my details. It wants me to sign in when I use it so that it can see what I listen to and see what else I might listen to next. I don’t really have any problem with this. I’m quite grateful for the way that YouTube looks at what I’m viewing and shuffles things that might be interesting in my direction. It’s a lot more intuitive than the way Google notices I’ve looked up an item of clothing and then serves me ad after ad featuring the same item, regardless of whether I’ve bought it and therefore no longer wish to know any more about it.

The BBC, like most pre-digital media owners, knew laughably little about its customers in the past. They couldn’t be bothered to capture any information about them and wouldn’t have known what to do with that information once they’d got it. They weren’t the only ones. I remember a lunch in the mid-90s with the boss of a major record company who had all the names and addresses of hundreds of thousands of members of Take That’s fan club. He knew that such a list ought to have been valuable or useful but couldn’t see how. Nor could I. Now the BBC, like the rest of us, wakes up in a world where the most valuable thing is not your content or your much-vaunted creativity. The most valuable commodity is the people you have relationships with. The inhibiting fact is that as soon as you start presuming upon that relationship too much, you no longer have it.

What’s in a name?

The Chalke Valley History Festival takes place every year deep in the Wiltshire countryside. The brainchild of the young historian James Holland, it cleverly combines the standard literary festival, where upper class ladies gather to listen to TV historians plug their latest books, with the military re-enactment caper, where choleric-looking blokes with handlebar moustaches coax ancient artillery pieces into action for the entertainment of small children.

Nothing puts bums on seats at events like this like anyone who can claim some link to the Last Unpleasantness with The Germans. This applies to the villains as well as the heroes. The son of Hans Frank, the appalling man who ruled Poland on Hitler’s behalf, was down to appear this year. At the last moment, he was unable to travel so the organisers managed to whistle up Katrin Himmler, a blameless political scientist whose great-uncle was the notorious Heinrich. In the writers’ green room, we were fantasising that somewhere there must be a subs bench where people who share surnames with lesser-known fiends are waiting to fly anywhere in Europe to send a shiver through a tent-full of people who know only about these events through literary festivals.

You never go hungry with a famous or infamous name. I was there to take part in a session about the 50th anniversary of “Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” with Giles Martin, the son of the man who produced the album of that ilk before he was born. I mentioned Sgt Pepper to a rather grand lady in the tea tent. She assumed I was talking about some chap who won the VC for knocking out a machine gun and said, “I’m sorry, I’ve never heard of him”. Good to know pop culture hasn’t entirely taken over the world.