If you ever visit a new mother in hospital, you will be impressed by how easily she can distinguish the cry of her own newborn from the apparently undifferentiated cacophony coming from the nursery next door.

It's like that with magazine editors. The perception of the paying customer is that there's not much difference between one magazine and its closest competitors. Of all areas of the media, consumer magazines are most likely to come in for the criticism "it's all the same". An editor will leap to put them straight on that score, often at uncalled-for length. According to them, their magazine is a quality product, head and shoulders above the opposition in both conception and execution. Its readers are more discriminating, its cover lines pithier and more witty, its staff more clever, its relationship with its people of a higher order than the blundering, benighted competition alongside it on the newsstand. It's clearly self-delusion, but on the back of such delusions does much media live, breathe and have its being.

The magazine editor must steer a ship between the Scylla of difference and the Charybdis of sameness. Some have found success at one end, some at the other; most have ended up somewhere in between. For instance, in a media landscape where people spend less time considering their buying decisions, it's never been harder to communicate a magazine's essential difference to the ‘moron in a hurry’ beloved of cliché in the place it most matters, on the cover.

Copying used to be slow to happen and tricky to execute. Now it's easy.

Middle of the road

I understand the process whereby all products cluster in the middle of the road is known as ‘saming’. We see it in supermarkets, where the adoption of best practice, the rate of imitation and the old fashioned fear of failure results in the vegetables always being over here and the wine always being over there, with the inevitable result that the customer neither knows nor cares which actual supermarket he is shopping in. Then he goes home and watches expensive television commercials telling him how one is qualitatively different from another. The marketing message is difference; the actual experience is sameness.

What we are seeing on the newsstands, and elsewhere in consumer markets, is the bitter harvest of our modern rush to competence. Copying used to be slow to happen and tricky to execute. Now it's easy. The hand and eye of a few great magazine designers used to mark out their work as better than anyone else's as clearly as a good chef's signature dish would taste better than the other guys'. In the new digital dispensation, everybody's worked out the recipe for Chicken Kiev and can bash it out endlessly, if that's what's required. A half-decent art director can ape the work of a brilliant one without too much trouble, and you or I probably wouldn't spot the difference.

At the same time, the range of subject matter within the pages of the magazine is relentlessly narrowed by the dictates of the marketplace, the requirements of advertisers, the arrival of new, more ruthless competitors like Richard Desmond (who's got no compunction about trumpeting the fact that the best thing about one of his magazines is that it's cheaper than Heat) and a growing cynicism about what readers can be expected to tolerate.

Margaret Thatcher's theory was that unbridled competition meant a profusion of variety. It doesn't.

Template publishing

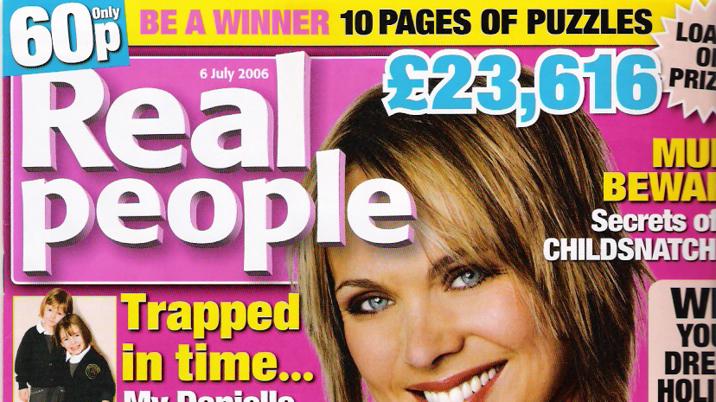

The covers of women's magazines used to offer an impression of variety because they were devoted to anonymous models. In this long-ago era (about ten years long-ago), it used to be argued that you could not have actresses or singers on the covers because they would hijack and subsume the magazine's individuality. But then the models started to have names like Cindy and Naomi and Elle, and it became a contest to see which of these supers the magazines could persuade to pose for their photographers. Then they discovered Liz and Kylie and Courteney could sell magazines for them and were perfectly happy to sell out any notion of editorial objectivity if it meant getting the right famous face on their cover. They took the old People magazine formula of ‘a famous, beautiful woman with a problem’ and peddled it ruthlessly, if not imaginatively. Then the new generation weeklies arrived on the same turf. They were working without the cooperation of the stars they featured. Which is why the standard template for a women's magazine now involves a hot pink logo, a precise number of pages of fashion and accessories all emblazoned across an agency picture of either Jennifer Aniston, Kylie Minogue or Angelina Jolie striding across a pavement on their way to some charity do. You will be invited to speculate on whether she is too fat or too thin, bravely coping with heartbreak or deliriously happy with her new man. The proposition gets narrower all the time. Which is similarly why the two men's weeklies, Nuts and Zoo, which began as fairly tightly defined propositions, have now, after only a couple of years, hardened into an even narrower formula in which one offers ‘100 Sexiest Footballers Wives’ while the other counters with ‘Keeley's World Cup Strip’.

What's behind all this saming? It's the same reason that movie magazines always lead with the new blockbuster months before people have had a chance to find out what a disappointment it is, the same reason that women's magazines keep coming back to the subject of weight, the same reason that men's fitness magazines always have a feature about losing your love handles, the same reason that car magazines lead with vehicles that their readers will never afford, the same reason that angling magazines always lead with a bloke holding a huge fish in his arms, the same reason that music magazines endlessly rotate Oasis, the Beatles, U2 and the Stones. Because, for the moment, it works. Keep doing the obvious and you will keep the customer satisfied, at least for the moment.

The very fact that InCirculation asked me to write this piece indicates a growing feeling that this state of affairs can't go on forever. The big publishers have spent the last five years engaged in a frantic land grab in the new weekly market that has emerged from the celebrity boom, the morphing of the teenage and young adult categories and the lowered age profile of the labour force. Other activity has been minimal. This weekly market has taken great chunks out of the monthlies that traditionally dominated with young adults. The monthlies, who previously lorded it, seem uncertain about how to respond to these chippier cousins.

Margaret Thatcher's theory was that unbridled competition meant a profusion of variety. It doesn't. Instead it has spawned an unprecedented degree of sameness. I thought some brave soul had finally made a stand when I saw the July issue of FHM which featured a tremendous picture of Beckham, Lampard and Gerrard instead of the usual minor soap actress in her pants. It seemed reasonable that Britain's most popular men's magazine should be confident enough to lead with the biggest sporting event on the planet (though obviously not in Scotland). But it proved to be an illusion. Flip FHM over and there's the real cover, featuring the usual minor soap actress in her pants.

You have to obey the rules of the category and the categories encourage sameness rather than variety.

Category dictates

Few people are trying to bend the categories, which is where the true growth has always occurred. When we launched Heat, the original intention was to appeal to women and some men. This proved difficult to achieve, partly because you eventually have to choose which part of WH Smith you wish to be displayed in, either among the women's titles or alongside the Economist and Private Eye. If you're ever thinking about launching a magazine, first thing you should do is go to WH Smith, have a look at the way the store is laid out and then decide where you want your title to sit. Once you've made your choice, you must accept that you will end up employing the triggers that work for the titles around you. If everybody else is overclaiming at the top of their lungs, it's very difficult to maintain a becoming modesty. The blandishments of the Burlington Arcade count for little in Walford Market. You have to obey the rules of the category and the categories encourage sameness rather than variety.

Away from the weekly market, the terrain in which the specialist monthlies previously put down roots is now affected by the impressive amount of free information and entertainment that is available in these subject areas on the web and the fact that older men, many of whom no longer smoke, don't go into the newsagents as often as they previously did. That's one of the reasons why web activity and offshoots like radio programmes become so important to magazines like the Word and Mixmag, in that they provide a means to remind even your committed readers that a new issue is out and they should buy it. Dennis have managed to establish the Week, one of the most genuinely differentiated propositions in the magazine category, by learning how to turn mild interest into subscription more effectively than most other publishers. Increasingly, the older male reader likes the magazine but has small taste for the actual experience of choosing it.

I took a break from writing this piece to visit a supermarket. The magazine run seemed as confusing and hectic as ever. However, it was nothing compared to the area where the yoghurts jostled for our attention and the staggering range of things called shampoo clamoured to convince us that they were the one true solution to dry, unmanageable hair. But I don't think we've yet got to the point where shampoo affects our culture. Whereas British magazines have traditionally reflected the vigour and variety of our many interests and obsessions. It would be a shame if they couldn't do so in the future.