A week after marking a quarter century working for Condé Nast, publishing director Stephen Quinn is in ebullient mood. The reason? A carefully folded piece of A4 he's just removed from his inside jacket pocket detailing the recent performance of the title on which he has worked for the past 21 years, British Vogue.

"Vogue must be one of the few publications at the moment to be able to say advertising and circulation revenues are once more what they were in 2008," he proudly declares. Even more gratifying - to 69 year-old Quinn, at least - is that the bulk of the title's not inconsiderable income still comes from … print.

With a typical double page spread in British Vogue currently selling for around £32,000, the title is now generating in the region of £25m a year, according to one recent report - though Quinn won't confirm precise figures. No wonder he describes the current climate for Vogue as "halcyon days".

Luxury sector

There are two reasons for this, he explains. First, the recession-defying strength of the luxury sector from where Vogue's advertisers come and to which its just over one million affluent, style-obsessed readers aspire.

"There's been phenomenal growth in luxury advertising over the time I've been here," Quinn observes. "Not so long ago, all of the leading brands - Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Prada, Dior - would have taken, on average, 20 pages each. Today, however, on average, it’s 50."

Which underlines the second factor he cites: the enduring power of the Vogue brand.

"It's all down to the power of the magazine. Vogue has fashion bible status. It is the place for trendsetting and top advertisers, and we live off our fashion credentials", he adds.

"You have to make sure you have brand leadership in fashion, and style, and ideas, and art direction, and that you use the best photographers, models and stylists. Compromise on this, or fail to have the best overall sense of the zeitgeist, and circulation will diminish."

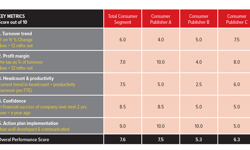

To guard against this, every 24 months, British Vogue undertakes an in-depth piece of market research - the latest is currently underway - assessing itself against a number of other leading British monthlies to ensure its focus remains sharp and current, and to demonstrate to advertisers it is indeed all Quinn claims it to be.

"You hope the eternal verities will prevail, that the leading luxury brand marketing directors we speak to will still vote Vogue Britain's top fashion magazine," he says. "The core question is: are those clients justified in still taking so many pages in Vogue? The answer you want is that Vogue is still best at creating the hunger for their brands and the particular lifestyle they represent."

It's a high benchmark but one which Vogue has achieved - and continues to maintain - through the power of print, Quinn believes, readily acknowledging how unfashionable this sentiment is in the current publishing climate.

"While 90% of the ad revenue Vogue brings into this building comes from print, just 10% comes from digital," he says, estimating that half of this digital income is Vogue-exclusive while the rest is from cross-brand digital campaigns.

Digital strategy

Condé Nast policy has been to extend its magazine brands online and onto tablets and smartphones, and Vogue has been no exception. First launched back in 1996, the Vogue website, www.vogue.co.uk, now enjoys 1.3m unique visitors each month.

Meanwhile, its iPad edition, first launched in 2010, then re-launched as a monthly last September, has a circulation just shy of 4,000. It's small beer when set against print sales of 203,356 for the second half of last year. But while print sales for that period were down 3.5% year-on-year, sales of the tablet edition are now growing fast.

Not so long ago, a YouGov survey of 2,500 Vogue readers showed that 87% most wanted Vogue in luxury print format while, in marked contrast, just 8% expressed a preference for digital.

Over the past 18 months, however, there has been a marked upswing in luxury brands - who've been notably late to embrace digital - clamouring for digital and cross-platform ad solutions. And this, in turn, has prompted the company's head of digital, Jamie Jouning, to recently announce he expects digital revenues to account for 30% of the total by the end of 2014.

The essence of print

So why, then, the enduring faith in print?

"Because at the heart of the Vogue brand is the printed product," Quinn replies. And because in the luxury fashion market, physical products best embody and convey quality. "No digital product can be as glamorous as print," he insists.

Besides, print and digital serve different roles. For while what's happening and latest developments lend themselves well to 24/7 digital platforms, print is the only place to address - and define - the zeitgeist, Quinn claims: "It is essential to feed the hunger that drives the brand - the readers' desire to be the person they aspire to be."

Magazines should be less shy of asserting their strengths, he adds, warming to this theme. "When you hear some of the young generation of publishers speak nowadays, it seems that they'd prefer just a token five or six thousand print sales with the rest digital," he observes.

"But what this shows isn't forward-thinking but a lack of appreciation for culture, art, design and layout - a kind of slightly ignorant obsession with process rather than inspiration and wonderful artistic flourishes and journalist intelligence. It's depressing."

Preserving integrity

So, too, is publishers' talk of '360 degree publishing', 'synergy' and the future potential of 'e-commerce'. In fact, worse, terms like these may even pose a threat - rather than a panacea - to the long term health of magazine publishing.

"Net-a-Porter treads a curious line between claims to be objective and detached in its reportage and its business model based around selling off the page," he says.

"I've seen interviews with people there called 'editors' talking about their love of the immediacy of their sales. But all that is is a great big money-making machine. And there is no sense that these 'editors' are on their readers' side."

With many magazine publishers now talking about selling products direct from the page, Quinn believes a big challenge for any future Vogue publisher once he steps down in two or three years’ time will be not to spread the brand too thin. Essential to Vogue's future, he says, will be: "to still be recognisable, to have an editorial product with independence and integrity, and so be a proposition readers can believe in and trust."

It's a philosophy evident in two current initiatives: the launch later this month (April) at the Queen Elizabeth Conference Centre of the second two-day Vogue Festival in central London and then, in May, publication of Miss Vogue in print and on iPad. Both were conceived by British Vogue editor Alexandra Schulman - the former to deepen the engagement between brand and reader by enabling them to meet leading figures from the fashion industry; the latter to introduce the brand to a younger generation of late-teenage readers.

The end game for Vogue Festival is the incredible publicity it creates which underlines Vogue as a powerful, influential magazine, says Quinn insisting that, though sponsored by Vertu, the event is anything but a commercial money-making exercise.

"Some publishers more modern, energetic and greedy might be tempted to swamp it with sponsorship of every kind," he explains. "But do that and readers won't be able to come and see Victoria Beckham or Donatella Versace without entering a fairground with everyone hustling them to buy something before they reach the auditorium."

Yes, Vogue Festival broke even in its first year. But the point is, it surrounds the magazine with "a sense of engagement and a halo of respect". Miss Vogue, meanwhile, is - for now, at least - a toe-in-the-water one-off rather than a full-blown attempt to roll out a British version of US spin-off Teen Vogue.

"Whenever we brought up the name 'Teen Vogue' here with advertisers, they felt it was too young and did not want their own brands delineated in that way," Quinn continues. "So when we revisited it last autumn, we came up with the idea of Miss Vogue - a single magazine to be poly-bagged alongside the June issue of British Vogue."

Past British Vogue supplements, such as Catwalk, have had a single sponsor which, in turn, received 16 out of a total pagination of 52 pages. But Schulman wanted to give Miss Vogue the look, structure and feel of a proper magazine.

This made it costlier and bigger - 116 pages, in all. However, within just two months of announcing the title, more than two dozen advertisers ranging from Top Shop and H&M to Burberry and Harvey Nicholls had bought 30 pages of ads - enough to cover production costs.

Again, he insists, the point of doing Miss Vogue at all is to see what it brings to the Vogue brand.

It's all part and parcel of safeguarding the Vogue brand's future health by maintaining its status, demonstrating its integrity and independence and strengthening its relationship with its readers.

"A future publisher will need to be committed to defending the editor and safeguarding their freedom against the challenges to independence and integrity posed once everything is dictated by numbers," he adds. "Because add-on products alone - the iPad edition, the iPhone app - will struggle to come anywhere near the profits we generate today."

Picture credit: Stephen Quinn (Campaign magazine)