Dave Calhoun, chief content officer of Time Out North America and UK, is recalling his early encounters with Time Out. “When I look back at myself as a 16-year-old in London in the mid-nineties, I was flipping excitedly through Time Out to find gigs, art shows and theatre,” he says. Time Out back then meant a print magazine. As of June 21, that magazine was no more.

Few now rely solely on print, the core Time Out audience of 18 to 34 least of all. “We’re increasingly thinking [at Time Out], where is the younger millennial audience and the gen Z audience getting inspiration for what to do in their cities?” continues Calhoun, “and it is not through magazines. It was a tough decision [to close the print title], but it was a positive decision – to make that break and focus on where our audience is and will be.”

A brief history of Time (Out)

Time Out was founded in London in 1968 by Tony Elliott, then a student, at his mother’s kitchen table, becoming as renowned for its investigations and radical edge, as it was for its listings. In the mid-nineties, when Calhoun first turned to it, Time Out London was in its heyday, with a weekly circulation of 110,000. This success encouraged the launch of Time Out New York in 1995, the first spin-off in more than 40 cities. Then came the internet. By 2012, circulation had halved to 52,000. The title needed a boost. That October, it dropped its cover price and joined the free magazine market.

Just before its closure, circulation was at 310,000, with the magazine being distributed each fortnight to Tube stations and arts centres like the Barbican. “The magazine was still really well-loved,” says Calhoun. “It was successful as well. Businesses loved partnering with us as a brand, which included the magazine. But it was becoming an increasingly small part of what we did and, at the same time, it was time-consuming to do it well. And there's nothing that we don’t want to do very well.”

This, for Calhoun, gets to the heart of things. The team, who worked largely across all platforms, from social and video to digital and once print, needed to concentrate their energy. “It’s not going to benefit the brand, it’s not going to benefit the quality of our content, it’s not going to benefit what our partners want from us, if we’re spreading ourselves too thinly.”

Calhoun has worked at Time Out group since 2005, when he joined the team as film editor for London. In his current role, which he started in April, he oversees content, strategy, direction and execution across the UK and North America. The gap between how the London and New York operations work is “pretty narrow… They’re both global, outward-looking cities.” But each team “breathes local knowledge”. They need people on the ground.

Lockdown lessons

Time Out London suspended its print magazines during the first lockdown, between March and August 2020. The pandemic accelerated the decision to stop the print issues long-term, but the decision was well on its way. “We had already been looking at where we could find our audience and where they were making their choices about going out and, less and less, it was through print. It was through our site or our social channels, and increasingly, through our video content… [Closing the magazine] was not a decision we made out of a crisis. It was a decision we made by thinking, what do we want to look like in 2, 3, 5, 10 years’ time?”

The advertising figures tell a similar story. During the six months to the end of 2021, print advertising rose 15 per cent to £1.67m, while digital advertising shot up 62 per cent to £8.89m. “Print was an increasingly small part of our revenue,” says Calhoun. “We wouldn't have made this decision if it wasn’t.”

The pandemic changed things for Time Out in a more substantial way. “As a Londoner, I do think the pandemic has really shaken things up,” says Calhoun. “The free magazine market is heavily based on people coming into city centres five days a week and that world has gone… The relationship between cities and print and commuting has changed enormously.”

What readers want, he adds, has also changed. During the pandemic, Time Out became Time In, winning International Brand of the Year at last year’s Campaign Publishing Awards for its transformation. Out went restaurant recommendations, in came pieces about new food delivery services. Out went gig suggestions, in came streaming ideas. As people were confined to their neighbourhoods, local coverage became increasingly valuable, leading the brand to start a strand called Love Local, highlighting independent businesses. The strand is still going strong. “[The pandemic] taught us to be even more nimble,” says Calhoun. “And it restated the importance of our relationship with our audience in providing a commentary on city life, whatever city life looks like at the time.”

Digital foundations

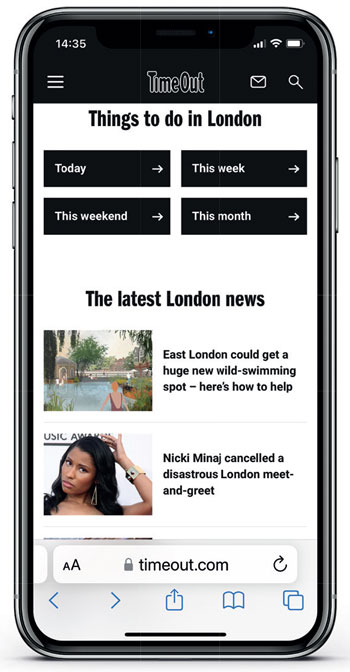

Time Out already has a strong online presence. The UK digital audience is rapidly growing, say the publishers, with monthly pageviews up 77 per cent and monthly visits up 46 per cent year-on-year. Time Out London has 1 million followers on Instagram, 1.4 million followers on Facebook and 1.5 million on Twitter, while followers on Time Out London’s TikTok account, which the team set up in May 2021, already number 96,000.

“The challenge for us now is what else can we do?” says Calhoun. “How do we engage people more with Instagram? How do we engage them with email? But we’re not doing this from a standing start. We’re already seeing about 10 million views a month on Time Out content just within the UK… Many, many, many more people already engage with us on these channels than they did through the magazine.”

This summer, the big push is video, driven largely by the success of Time Out London on TikTok, where the launch of a Greggs and Primark collaboration attracted 3.2 million views, the launch of Criss Cross café, London’s first croissant café, another 3.2 million views and the UK launch of Popeyes, a fast food joint, 1.1m views. Calhoun wants to replicate this on other platforms. The team already publish videos on their site and across other social accounts, but audiences can expect a lot more.

Time Out New York, points out Calhoun, has seen particular success for its videos on Instagram, with launches of restaurants and openings of events like a roller disco at JFK doing especially well. They didn’t go back to print after the pandemic, and Calhoun has been buoyed by how well they have still been able to engage with both their audience and their clients.

The Time Out London team are now busy making both one-off videos and series, including Secrets of the City (taking people behind the scenes of a landmark like Big Ben) and What I Eat in a Day (neatly summed up by the title). Six short video series will be launched over the next couple of months. “We’ll see what engages our audience and develop ideas from there,” says Calhoun. “The ones that are less appealing we’ll drop and find some more.”

Cornering the market

Digital is only part of the story. Time Out Markets, showcasing “the best of the city under one roof”, have also been marked for expansion. The first market, which opened in Lisbon in 2014, quickly became the city’s most popular attraction with 3.6 million visitors a year. Now there are markets in New York, Boston, Chicago, Miami, Montreal and Dubai. Osaka is on the cards for 2024, with London the following year (negotiations are under way for a spot).

Each market comprises about 20 bars and restaurants, as well as hosting comedy nights, talks and gigs. “There is a strong sense of editorial curation,” says Calhoun. “They’re everything we love about the city brought to life in a permanent venue.”

Offering experiences, he adds, “has turned out to be one of the strong elements of our future”. While people in London wait for a market, they can still go to one-off events like The Tasting Sessions (an event matching chocolate cocktails) and Hotboozapalooza (hot cocktails this time). “We’re in our audiences’ lives celebrating going out, so it’s natural to sometimes create those events,” says Calhoun. “This is not a sideshow for us. It’s absolutely what we’re about.”

Time Out is currently undertaking a big piece of research looking at how people are making decisions about how they spend their time post-pandemic. But Calhoun has his own future barometer lined up. “I’ve got a 10-year-old daughter and I think to myself, ‘When she is 16, 17, 18, where is she going to be getting her inspiration to go out in the city? I hope it’s Time Out. By then, TikTok’s probably going to be old hat. Who knows what our relationship will be like with Instagram and Facebook? Wherever it is, we have to be ready and, to be ready, you have to be open to constant innovation and change. You also have to be ready to let go of elements of your portfolio that no longer feel like the future.”

Today, that element is print. In a couple of years, it could be TikTok. In a decade, Time Out could have joined and left the metaverse. “What does Time Out look like in the metaverse is a question we’re asking ourselves,” says Calhoun. “Have we come up with an answer so far? No, but it’s important that we’re asking the question.”

This article was first published in InPublishing magazine. If you would like to be added to the free mailing list to receive the magazine, please register here.